The Staneyhill stone (and round about)

By Sigurd Towrie

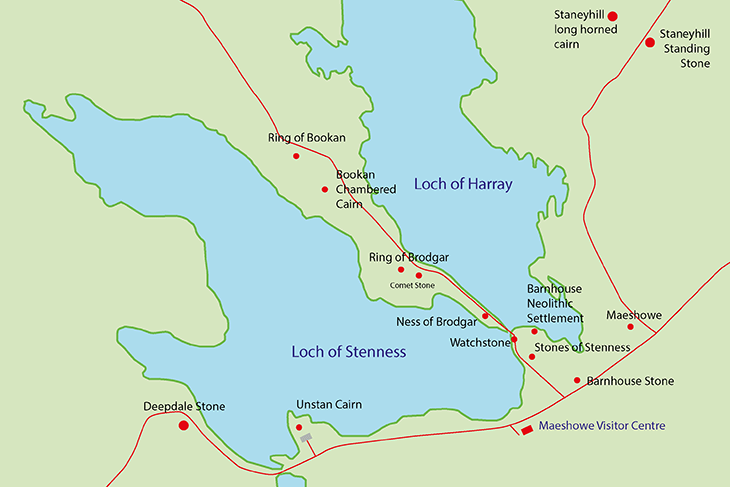

A solitary megalith towers over a Neolithic quarry about 350 metres to the south-east of the Staneyhill horned cairn.

In 1865, the Orcadian antiquarian George Petrie referred to it as the “Stone of Gramiston” [1], while, in 1903, we find it called the “Stane o’ Hindatuin”. [2]

Today it is best known as the Staneyhill stone.

Situated on private land, the pointed megalith stands over two metres high [3], is around one metre at its widest and 30 centimetres thick.

In 1923, Fraser described it as a “well-defined landmark about ten feet in height and is situated about forty yards east of the Harray to Stenness road.“ [4]

He added:

Although the monolith stands above an exposed rock face, it was not quarried from it. Instead, geological examination suggests it was sourced from the rocky outcrop adjacent to the Staneyhill horned cairn. [5]

This has intriguing parallels with the known megalithic quarry at Vestrafiold, where standing stones were extracted from an outcrop also associated with a horned cairn. [6]

But although the quarry beneath it was not the source of the Staneyhill stone, it was probably used for monumental construction – in this case Maeshowe, just under two miles to the south.

The wedge-shaped blocks of fine-grained sandstone characteristic of the outcrop match those within the chambered cairn’s central chamber.

A saint’s cortege

In the 12th century, the remains of Earl Magnus Erlendsson (Saint Magnus) were moved from Birsay to Kirkwall. As a result there are numerous locations traditionally said to be the resting places of the saint’s cortege.

According to the Orcadian folklorist and historian George Marwick one of these stops was at Grimeston, in Harray, where a “large stone” was raised in commemoration. [7]

In his 1902 paper on Birsay traditions, Marwick does not specifically pinpoint the Staneyhill stone and appears not to have known its location:

By 1903, however, the Staneyhill stone had been firmly linked to the relocation of the saint’s remains.

Citing George Marwick in his Birsay Church History, Rev Goodfellow declared:

Stone circle?

Among the ideas attached to the Staneyhill stone over the years is that it was part of a stone circle.

Although the area has not been excavated, the notion of a ring of stones is tenacious:

More megaliths…

The area around the Staneyhill megalith is packed with archaeology – not only numerous mounds and barrows, but other possible standing stones.

At Feolquoy, south of the monolith, there was a “standing stone of small dimensions”, which had been removed by 1923 [4]. West and north-west of this area is a cluster of tumuli, probably Bronze Age barrows.

Half-a-mile to the north-east of the Staneyhill stone, near the farm of Appiehouse, is a huge mound crowned by a triangular-shaped megalith.

In 1923, this stone was recorded as being “about 4 feet in height and 4 feet in breadth” [4]. In 1946, its dimensions, as documented by the Royal Commission for Ancient and Historical Monuments Scotland (RCAMHS), were “2ft 9in high, 3 feet wide at the base and about 6.5 in in thickness.”

The mound was considered to be natural until 2005, when structural features were partially exposed within. These may relate to a Maeshowe-type chambered cairn.

To the north-east of the Appiehouse mound/stone is the site of another possible monolith.

The stone, “on the farm of How” had, by 1923, been “broken up and removed in the course of farm improvements”. [4]

Going by 1923 memories of its name – “Fa’an or Faal Stane o’ How” [4] – it may well have been a toppled standing stone. “Fa’an” is dialect for “fallen”, suggesting the stone had once been upright. Unfortunately, we know nothing else about it, but the placename How/Howe strongly suggests the presence of a substantial mound in the vicinity.